By Jim Algie

In the middle of 2011, some eight years after the Thai government’s “War on Drugs” stacked up a body count of 2,500 people in three months, the first and only policemen to be indicted were handed down two-year sentences for shooting a nine-year-old boy caught in the crossfire as his mother, an alleged drug dealer, sped away in her car.

In the middle of 2011, some eight years after the Thai government’s “War on Drugs” stacked up a body count of 2,500 people in three months, the first and only policemen to be indicted were handed down two-year sentences for shooting a nine-year-old boy caught in the crossfire as his mother, an alleged drug dealer, sped away in her car.

The boy was shot as he sat in the backseat. His mother’s body has never been found.

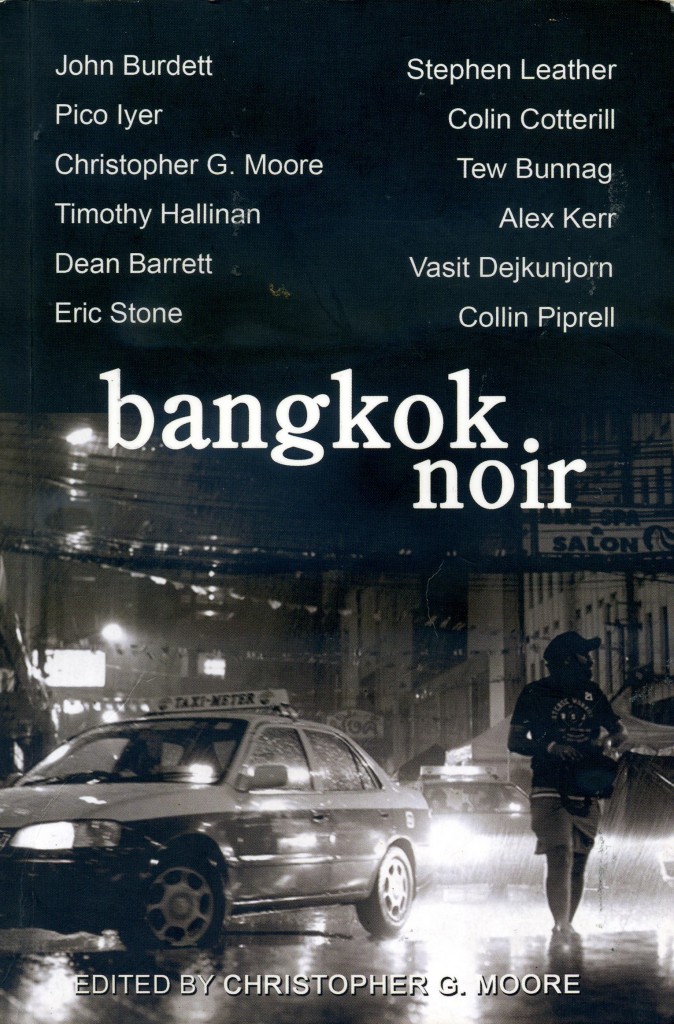

It would be hard for any hardboiled author of crime fiction to compete with such front-page stories, but convictions like that, or even investigations, are rare. Most crime stories disappear from the press within days, leaving journalists to grope for euphemisms and nebulous terms like “invisible hands” and “dark influences”, while the general public has to read between the lines or consult some of the internationally heralded authors in the anthology Bangkok Noir (Heaven Lake Press, 2011) for all the gory details.

At first glance, the title reads like an oxymoron. Given the sunny climate and the sunny-side-up dispositions of most Thais, invoking the word noir next to Bangkok seems a mite strange, because the French word for “black” is more a state of existential despair than a genre of film and fiction. In response to two World Wars and the Great Depression that carved a long dark trench between them, much of the crime fiction and cinema of suspense from the ‘40s and ‘50s was infected with a lethal strain of fatalism.

It’s a bleak worldview best represented in this collection by Timothy Hallinan’s “Hansum Man”. The author of “The Queen of Patpong”, a 2011 nominee for the Edgar Allan Poe best mystery novel award, tells the punchy tale of a Vietnam vet coming back to Bangkok in search of R ‘n’ R after a long time away, only to find a city that is more hostile and foreboding than he remembered. True to the genre’s downwardly mobile nature, the only way for the protagonist to go is to go down screaming blue murder.

Noir’s elasticity is stretched in engrossing new ways by the book’s editor, Christopher G. Moore, in “Dolphins Inc”. Displaying the author’s penchant for melding contemporary concerns like the annual dolphin slaughter in Japan with the imaginative realms of cyberpunk and hardboiled fiction, this genre-jumping tale rewards repeat readings. In fact, I’d challenge anyone to figure it out the first time around.

That stock character of noir, the femme fatale, gets revamped in Thai fashion. John Burdett (Bangkok 8) adds a few touches of tastefully written erotica to a portrait of Thailand’s most infamous female phantasm in “Gone East”, while the eminent travel author Pico Ayer (Video Nights in Kathmandu) returns to the Bangkok scenes of that non-fiction collection in the only story that flirts with the city’s main tenderloin for tourists.

Penetrating the love lives of Thai society’s elite is a subject rarely dealt with in English-language writing from Thailand. Until now, as local author Tew Bunnag sketches the incongruities and murderous passions in a love quadrangle of an older, bisexual politician, his younger mistress, an errant gigolo and a forsaken wife in “The Mistress Wants Her Freedom”. Tew’s sympathy for the plight of the young mistress at the hands of the Viagra-gobbling politician is rendered explicitly well: “He merely needed her to be there as a beautiful trinket to bolster his esteem and as a receptacle into which he could pour his artificially stimulated desire.”

The run up to any election is known in Thai slang as the “killing season” because that’s when the goons and hitmen intimidate potential candidates or eliminate political rivals. Last year’s election was no exception. The Royal Thai Police offered cash rewards of up to 100,000 baht for information leading to the arrest of 112 hitmen. The police also distributed posters of the wanted men across the country.

Pol Gen Aswin Kwanmuang was assigned by the former Deputy Prime Minister Suthep Thaugsuban to keep an eye on the country’s contract killers in some 50 potential flashpoints. Leading a team of 60-odd investigators, the policeman told The Nation. “Suthep wants me to monitor hitmen and figures with dark influence during the lead-up to the balloting.”

There it is again – that term “dark influence” – which rarely comes to light in any newspapers. But a few of these shadowy killers from the margins of society are fleshed out in the anthology by veteran expat authors Collin Piprell and Dean Barrett, who zero in on a stock figure of crime writing. “Hot Enough to Kill” by Piprell deglamourizes the hitman. To Chai it’s just another job that pays better than menial labour. At the end of the workday all he wants is do is have a cold beer and flirt with some good-looking women, like many other working stiffs.

In “Death of a Legend”, Barrett supplies the book’s cleverest and most Hitchcockesque plot twist, with the noir served up in dollops of black humour.

Stephen Leather and Colin Cotterill turn in entertaining yarns in line with their international reputations, but the riskiest story may very well be Pol Gen Vasit Dejkunjorn’s “The Sword.” Of all the different crime and detective stories set in Thailand, the police procedural is off limits, for the simple reason that any author revealing the behind-the-crime-scenes machinations of the force’s do-badders would be bringing down a death sentence on their own heads.

In all of the country’s Thai and English newspapers, the editorial is a yearly déjà vu – “Police in Need of Reform” – but how does the corruption play out on a daily basis? Vasit, a retired police general named a National Artist in Literature in 1998, fills in the blanks and grey areas of a young cop’s rise to riches:

“He did not forget that criminal investigation and interrogation alone were not sufficient for his fame. To be hailed as a police idol, he would have to show that he was skilled too in crime suppression. The young superintendent consequently turned to the easiest prey: the petty thieves. His arrest records were impressively long. When an armed robber resisted arrest, Yuddha did not waste time negotiating. The robber was gunned down in a brief firefight. With the extrajudicial killing, Yuddha joined the prestigious class of police exterminators.”

“The Sword” – a reference to the ceremonial offerings given to graduates of the police academy by a member of royalty – takes the case of a tycoon whose driver has possibly caused the death of a motorcyclist and expands it into a much bigger tale that details how the bribery system works. Unexpectedly moving in places and impressively detailed, the story’s climax turns it into a chilling cautionary tale.

After the canon of noir’s greatest exponents, the American novelists Jim Thompson, Chester Himes and David Goodis, ran out of firepower and readers as the ‘60s came to a close, a new kind of crime tale emerged, typified by Elmore Leonard, Carl Hiaasen and the early films of Quentin Tarantino, which plays the darker elements for black comedy.

As the new depression deepens and spreads like an oil spill, only the loan sharks and pawnbrokers are laughing now. So the stage is set for a return to noir’s pessimism, which is all about corruption: corruption of politics; corruption of big business; the commodification of human relationships; and ultimately, the corruption of the individual’s integrity and most cherished beliefs, as happens to the crooked cop in “The Sword.”

After all, in a country and body politic where the default prime minister is a convicted criminal on the lam, noir remains the tell-tale art.

(This is a slightly revised version of an experimental sort of book review/true crime hybrid that recently appeared in The Nation with a different title at: http://www.nationmultimedia.com/life/Black-is-back-30181824.html)